I Look at the Moon and Think about My Daughter-in-Law

Noa Eshkol

Solo exhibition

22 January – 19 March 2017

Curator: Roos Gortzak

The exhibition I Look at the Moon and Think about My Daughter-in-Law by Noa Eshkol consisted of two parts: an alternating presentation of her tapestries in the Vleeshal, and a selection of film and archival materials at Kunstverein Amsterdam. At the opening of this two-part exhibition, a selection of her dance compositions was performed by the current members of the Noa Eshkol Chamber Dance Group: Mor Bashan, Noga Goral, Rachel Nul-Kahana, Ruth Sela and Dror Shoval.

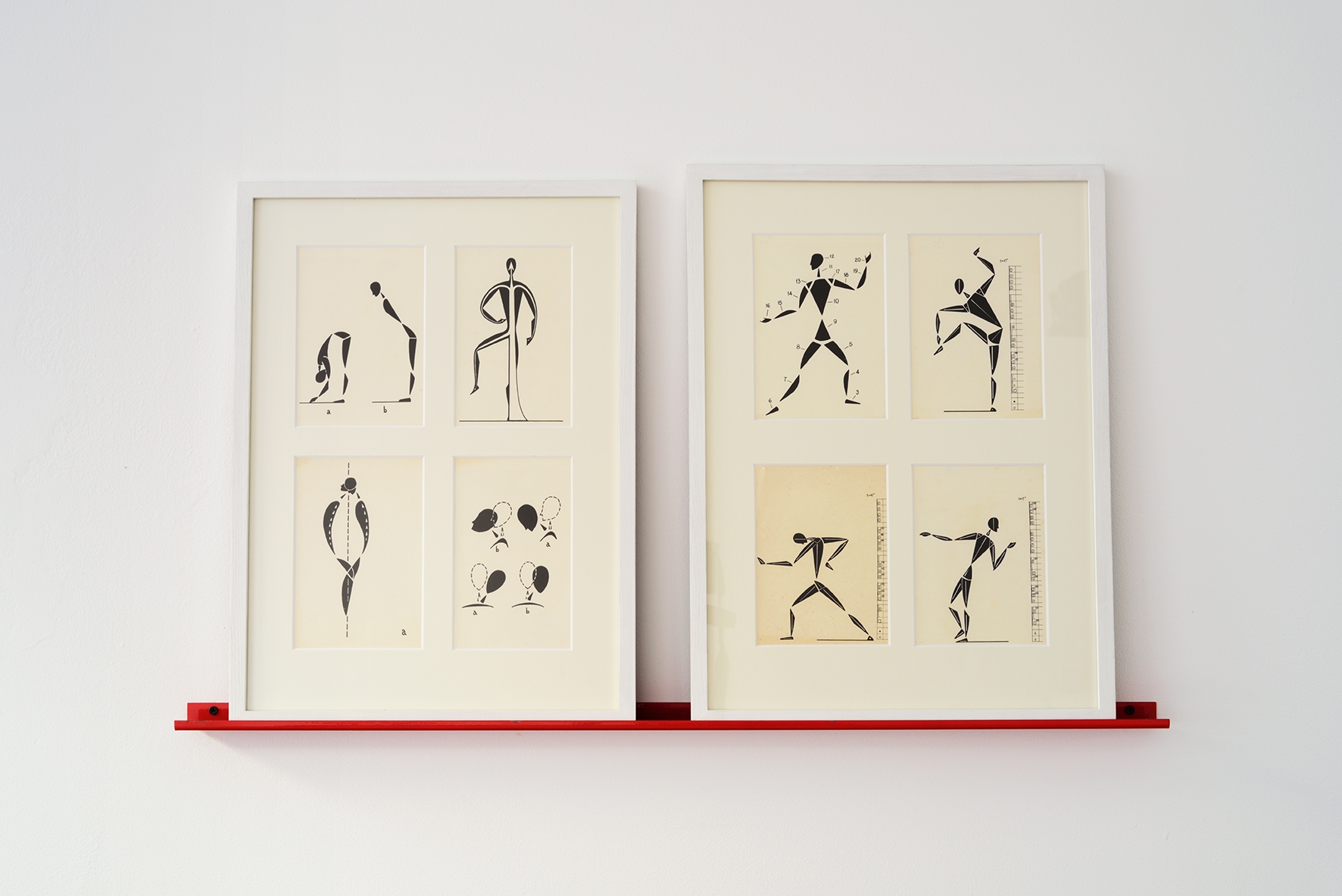

From 1954 to 1994, Eshkol created about fifty different dance compositions using the Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation (EWMN) system. Disappointed with existing dance notation systems, such as Rudolf von Laban's 'Labanotation,' Eshkol developed this new notation system in collaboration with the architect Abraham Wachman. She sought to create a method of describing the transitions between movements in the most accurate way possible, as opposed to the typical process of notating fixed poses that ignored the transitions from one position to another.

The unique EWMN system uses numbers and a small alphabet of symbols within a grid pattern. It provides dancers and choreographers with a systematic tool for composing and notating dance and all other forms of movement.

The conceptual value of the EWMN system lies in its use of an abstract model based on the universal language of geometry and mathematics. This allows for an objective visualization of all kinds of movements and their combinations, including movements that have yet to be discovered or cannot be captured in words. The potential of the EWMN system paves the way for countless applications. It can be used as a tool to study our own behaviors and interactions with the environment. It can also be applied to other fields, such as the study of animal behavior, autism, and sign language.

The title of the exhibition shows how imprecise sign language sometimes was and how necessary a more precise system of movement is. The sentence that had to be translated into sign language was: ‘I look at the moon and think of my bride.’ What came out of the sign language translation was: ‘I look at the moon and think of my daughter-in-law.’

The dance compositions are intentionally minimalist. They are not accompanied by music, except for the ticking of a metronome, and there are no elaborate, colorful costumes or sets. In almost all of Eshkol's choreographies, there is a common form of dance that consists of a sequence of interactions between multiple bodies in space. Artist Walead Beshty wrote in a catalog essay about her work: "The movements in Noa Eshkol's choreography announce themselves as gestures through repetition and synchronization, much as 'pa/' is a sound and '/papa/' is a word (according to linguist Roman Jakobson). And yet the gestures don't refer to anything specific, which would be like 'dad' never reaching the status of a word. It is a continuous state of motion.”

Eshkol worked with a small group of dancers who did more than just perform her choreography. The Noa Eshkol Chamber Dance Group functioned as a close-knit community. The members came to her home daily and were deeply involved in all of her projects. They performed a wide range of tasks, from research and archiving to cleaning, keeping journals, and assembling her tapestries.

In 1973, Eshkol temporarily stopped creating dance compositions. The only male member of the Noa Eshkol Chamber Dance Group at the time was drafted into the military during the Yom Kippur War. She felt unable to create choreography without him. She began to make tapestries, a new form of composition. Although the minimalist choreographies and her colorful tapestries may seem like two different creative expressions, they are in fact directly related, both in origin and in nature. In making the tapestries, Eshkol followed a strict set of rules: no alteration of the textiles she found or was given, no use of animal prints or textiles depicting human bodies, and no preference for any particular shape or color. In an attempt to avoid a subjective approach to the creative process, she said: ‘The material dictates what I will do.’ Mooky Dagan, with whom she worked for many years and who is now the president of the Noa Eshkol Foundation, said that it was frustrating for her not to understand what she was doing when making the tapestries. The opposite was true when she made her dances, where she followed her own system.

After about forty years of creating dance compositions, with a twenty-year overlap, Eshkol finally traded choreography for these colorful abstractions. In essence, they are part of the same carefully organized body of work: both follow strict rules, and both involve the organization of limbs and the repetition of gestures. But above all, they share a common purpose. In creating these compositions, in performing her dances, or in experiencing them, her work provides a filter through which to understand and shape the world around us, which sometimes overwhelms us.

Eshkol continued to make tapestries until her death in 2007, resulting in hundreds of works. The exhibition at Vleeshal featured a wide range of styles from different periods, from the very first abstract tapestry, aptly titled The First Carpet (1973), to the later Sunset by the Lake (1995). Although made in a horizontal position, Eshkol's tapestries were designed to hang on the wall like paintings. She also liked to see them displayed on the floor. At Vleeshal, the tapestries were displayed in both configurations. Each week, the presentation of the tapestries in the exhibition changed. The public was invited to choose a tapestry they would like to see in a vertical, standing position. This allowed for a continuous ninety-degree rotation, even though the dancers were no longer present. Handing over the composition of the exhibition was in keeping with Eshkol's non-hierarchical approach.

The Noa Eshkol Chamber Group performing a selection from their suites

From February 4 February until 19 March the second part of this exhibition took place at Kunstverein Amsterdam (curator: Maxine Kopsa). Kunstverein exhibited a generous selection of scripts that notate the behaviour of different animals, and the attempts researchers made to improve the language of the deaf-mutes, among others. There were also three films shown that were never screened before outside of Israel, capturing early recordings of Noa Eshkol and her dancers making use of the EWMN system as well as a chameleon on a branch. These films were screened on the window of Kunstverein’s storefront in the heart of the Jordaan, enabling both viewers inside and outside the space to be absorbed by the hypnotizing dances.

Photo: Kunstverein

Photo: Kunstverein

Photo: Kunstverein

Persons

This project was made possible by the generous support of the Mondriaan Fund, the municipality of Middelburg and the Embassy of Israel in the Netherlands.

Vleeshal also extends thanks to galerie neugerriemschneider.