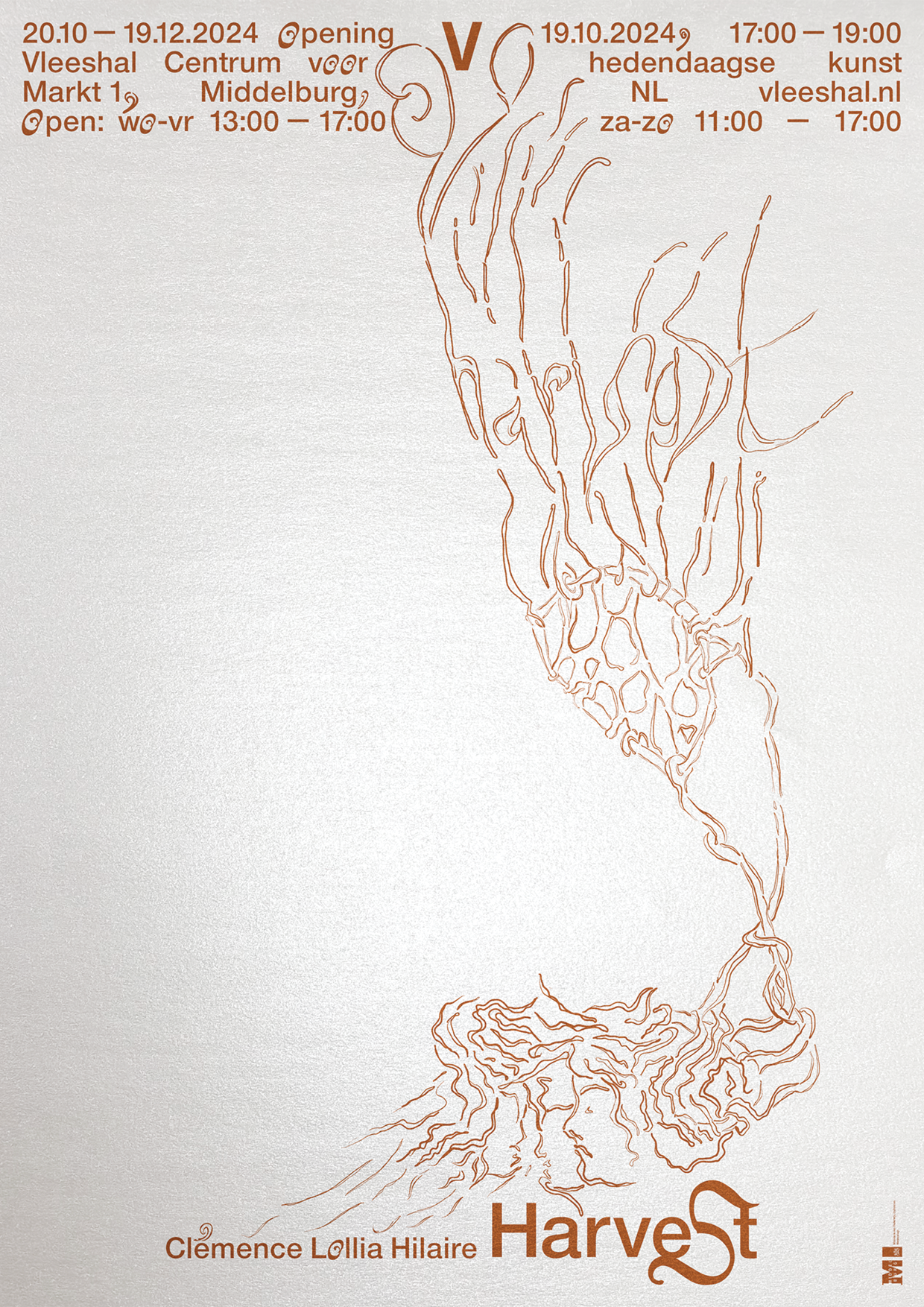

Harvest

Clémence Lollia Hilaire

Solo exhibition

20 October – 15 December 2024

Vleeshal (Map)

Curator: Roos Gortzak

Dear visitor,

The exhibition of Clémence Lollia Hilaire at Vleeshal presented the video work Harvest, accompanied by four sculptural elements. The video brings Arnacha, Betsey and Lucy back from the dead; three young women who were key to the development of modern gynaecology in the nineteenth century in the Southern United States.

Based on personal experience and supported by research on links between nineteenth-century Black women’s bodies, modern gynaecology, pain thresholds and the manifestation of this genesis in contemporary medical practice, Harvest merges some of the artist’s documented attempts to diagnose the condition behind severe chronic pain, with a B-movie-like revenge from the three living dead teenagers in a fertility clinic. In this clinic, their wombs are used as incubators for the cultivation of a crop – an extractive industry whose purpose is not clearly explained to them nor to the viewer.

Vleeshal, once the meat market inside of the former town hall, was where local butchers conducted their trade for centuries, with animal carcasses hanging from the ceiling.

Where does a body become flesh? In a meat hall, among other places, where it is marked, skinned and cut apart. Once stripped from being a unified whole, body becoming flesh can be processed and sold.

There’s something evocative about seeing a zombie film in a former meat hall. Flesh is the very thing zombies are made of, doomed to decay for eternity. Flesh is also their main worry, what they crave. But this hasn’t always been the case throughout the history of the genre. Think of Night of the Living Dead (1968) by George A. Romero. It is the first zombie film depicting living dead as cannibals, more than thirty years after the apparition of the genre in 1932 with Victor Halperin’s White Zombie.

The zombie film as a trope finds roots in western misinterpretations of various Haitian spiritual and herbal practices, described in William Seabrook’s travelogue The Magic Island (1929). The White Zombie reproduces on screen what Seabrook had claimed to see in US-owned plantations and sugar factories: 'enslaved voodoo workers' or 'zombies', stripped of their free will by means of black magic. The stereotypical depiction of Vodou, a legitimate religion like any other, was thus kickstarted by Seabrook and vehiculated further by many early zombie films, such as I Walked with a Zombie (1943). It can be considered a cultural punishment, of a similar nature to the financial debt imposed on Haiti after becoming the first Black Republic of the ‘New World’*.

Think again of Night of the Living Dead, the first cannibal zombie film: similar to the westerners' fears of a new Black Nation manifesting in the figure of the zombie, the late introduction of cannibalism within the trope can be seen as a setback from earlier moments of colonisation of the Caribbean, and projecting the inhabitants of the region as savage cannibals.

Almost a hundred years later the now-popular genre of Zombie films seems to have lost any connection to its anti-black genesis. But that is if – despite all evidence – one decides to stick to an arrow-like grasp of events and time. The dead are not coming back because they never left.

It is probably according to the latter premise that Lollia Hilare’s Harvest uses zombie tropes to re-flesh out Arnacha, Betsey and Lucy. Experimental, non-consensual and anaesthetic-free surgeries conducted on the three teenagers held in bondage improved knowledge in this branch of medicine, which was new in the nineteenth century. While very little is known about them, the doctor performing these surgeries was propelled to fame and is still known as the father of modern gynaecology.

The ‘fleshness’ of the zombie finds further meaning here with the distinction made by Hortense Spillers between body, a liberated subject position, and flesh, the ‘zero degrees of social conceptualisation’ necessary for the formulation of the free-willed body**. Freedom and its conceptual apparatus were built upon the subjection of the material black flesh. This dynamic complicates the gendering of Black women, making them stand outside ‘the norms of womanhood’, while effectively turning their bodies into living laboratories for modern progress***.

In an elliptical loop between each repetition of the film, the girls seem to be reduced to eternally inhabiting the clinic’s waitingroom. Anarcha, born around 1828, is making TikToks to kill time. Lucy is more accepting of her fate, while Betsey loses patience and initiates the murder of their captor. A toothless revenge, the making of which felt nonetheless more efficient for the artist than a pain reliever.

The revenge and cannibalisation of their oppressor by Arnacha, Betsey and Lucy is a way to ‘claim the monstrosity’ imposed onto their bodies assigned as ungendered flesh, impervious to pain. To eventually reimagine a radically different empowerment; formulate a Black female futurity that hasn’t yet happened but must be****.

At Vleeshal, another raw material substituted the water from three waiting room water dispensers, a generic object in medical institutions, and a signifier for time spent waiting - for a diagnosis, for a cure to once and for all get rid of the ‘inherited burden that black women in the nineteenth century carried with them about their gynaecological illnesses and the pain they felt: silence and dissemblance’*****.

A total of 230 cups were available in the space to consume medicinal plants preserved in white rum, as a promesse. By quenching the thirst of 230 ancestors suffocated on board of the slave ship 'Middelburgs Welvaren', which left Walcheren in 1750, the work committed to engaging in the long-overdue space that exists between binaries and dualisms—life and death.

The seaweeds featured in the sculpture and film were harvested in a monoculture in Zeeland, just a few kilometres from the Vleeshal, near the departure point of ships that once set sail to abduct their labour force for the New World before completing their journey back to Europe.

Reflecting on the connections to these natural resources, I’ll leave you with a diary entry from the author of Harvest.

Yours,

A distant relative

April 20, 2023

Serooskerke, Zeeland

That day of harvest in spring. I was excited to finally be on the boat’s slippery deck. Sitting for the two-hour drive to reach the farm was unbearable.

The engine started and the crank was now slowly turning and steadily dragging out of the water metre after metre of viscous brown strands of weed we had come to collect.The farmer was pulling them on board.As I tried to do the same, grabbing on the slimy rope made the pain even sharper, reminding me of the hysteroscopy the day before - of the metallic tool and its telescopic camera trying to intrude the opening of my cervix and carry out the most literal inspection I had ever experienced and simultaneously witnessed. Unfortunately, nothing could be seen, no diagnosis could be made, and I was told to go back to my GP. Another tool was used to fish out samples of tissues from the womb and left what felt like a sharp scratch.

Earlier this year, debilitating pain had given me some sort of fever dream and visions of what might be going on inside. I pictured tangled tissue of brown flesh wrapped around my reproductive system and obstructing the functioning of my nearby organs.

The motion of the crank stopped, the extraction paused. It took us a while to identify the issue, as we slowly drifted away from the crops. The weeds had gotten tangled in the engine. Passing a blood clot. Once freed, the propeller spun at full speed, creating a trail of white foam stained by torn fibres of weed.

The rather unusual experience of that day might be the reason I felt we were not that different. The weed and I. Bodies that look like mine were thought for centuries to be more adept to absorb pain, the weeds here were cultivated here for their absorbent properties.

* manuel arturo abreu, Rot Semantics, Zombie Reader, Cassandra Press, 2022

** Hortense Spillers, Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987

*** Ibid

**** Ibid; Spillers’ conclusion in the same essay finds strong echoes Kathryn Yusoff’s argument on 'Insurgent Geology’, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, University of Minnesota Press, 2019

***** Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology, 2017

Commissions

This project was made possible by the generous support of the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science and the municipality of Middelburg.